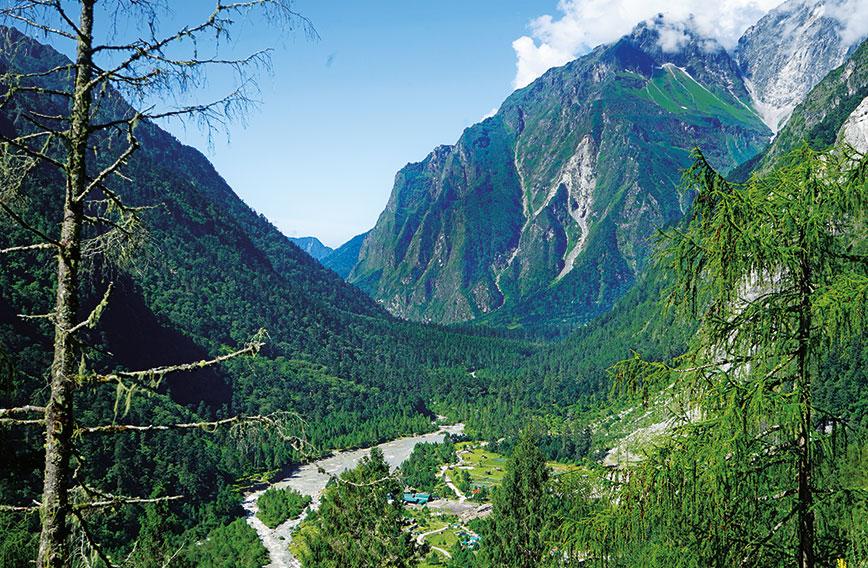

The Himalayan region states have 30 percent of the forests, 32 percent of the carbon stock, 36 percent of India’s biodiversity

Heavy-lifting mountains deserve rewards

P.D. Rai & Sushil Ramola

The states and areas of the Indian Himalayan Region (IHR) represent a substantial part of India’s forests, water sources and biodiversity. Together they account for 16 percent of the country’s landmass. But these regions remain poorly developed in comparison to most states and are inadequately represented in Parliament. As a result, in the give and take of federal equations, they have traditionally fared poorly. There is little understanding of their special needs and their voices when heard aren’t adequately accounted for. Landlocked, denied old trade routes, and custodians of natural wealth they must preserve, the mountain states are in urgent need of national attention.

What exactly is the IHR? It comprises the mountain states of Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Sikkim, Meghalaya, Nagaland, Manipur, Arunachal Pradesh, Tripura, Mizoram, the districts of Dima Hasau and Karbi Anglong in Assam, and Darjeeling and Kalimpong in West Bengal and the newly formed Union Territories of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) and Ladakh.

The diverse altitudes and agro-climatic zones, glaciers and river sources, biodiversity, cultures, tribal traditions, languages, dialects and remoteness make this region unique in its natural assets and cultural heritage and yet less developed and less understood. With 16 percent of the area, it contributes only four percent to the population of India. On the other hand, 30 percent of the forests, 32 percent of the carbon stock, 36 percent of India’s biodiversity are found here. Rivers originating in the Himalayas account for 56 percent of the river catchment area in the country.

The ecosystem services the region provides to the country are not immediately understood or valued but are vital to the well-being of the nation.

These states are landlocked. Before 1947, there was a lot of inter-country trade from the border passes like Moreh in Manipur and Nathu La in Sikkim. Burma teak was a famous import. Tibetan wool, imported via Nathu La, was the input for all kinds of carpets and other products in the region. The closure of the borders has meant that for all goods and services as well as markets for any produce one has to look to the ‘mainland’.

This has in many ways stymied the development trajectory of the region.The development potential of the region is further negatively affected by inaccessible terrain, severe climatic conditions, proneness to disasters, low population densities, poor connectivity and infrastructure, and central laws disallowing usage of forests that cover about 70 percent of the land.

This has led to extreme financial dependence of the Himalayan states on the Centre. Relative lack of economic activity has caused extensive out migration. With climate change threatening water resources and agriculture, migration has increased. As per the HIMAP study conducted by ICIMOD (International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development) which concluded in 2019, even if global warming can be restricted to a 1.5 degree increase by the end of the 21st century, temperatures will rise by 2.1 degrees in the Himalayan region which will mean large-scale melting of glaciers and a serious threat to water security not only for the people of this region but foremost for North India.

WEAK VOICE AT THE CENTRE

In our democracy, where representation in Parliament is proportionate to population, the mountain states individually and together have a very weak voice. Uttar Pradesh (UP) alone sends 113 MPs to Parliament (80 to the Lok Sabha and 33 to the Rajya Sabha). In comparison, the 10 mountain states, excluding J&K and Ladakh, but including the districts of Darjeeling and Karbi Anglong, send 35 MPs, including 22 to the Lok Sabha. UP has 15 percent of the Lok Sabha of 543. The mountain states combined have only four percent. Add to this the fact that the MPs from the mountain states are often from diverse political parties and it is not difficult to see why the voice of MPs from the mountain states is rarely heard on matters of import.

Subjects for discussion and debate are also politically driven. Unless there is a massive problem like insurgency there is very little effective reflection in the House about the development needs of this region. Further, there is huge asymmetry of power between the Centre and the mountain states. The kind of technologies and market-driven mechanisms that are defined in Delhi do not necessarily work in the smaller, sparsely populated states in the Himalaya which are very different from each other in addition to facing vastly different challenges than the plains.

The point we are driving at is that sustainable development agenda or any other agenda for the mountain states will not be brought up and given any weight unless there is a concerted effort by the majority party or a large number of MPs across parties and states. This is hard to achieve even in the best of times.

In times of crisis like the current economic crisis in which the world is floundering due to the coronavirus pandemic, the situation of the mountain states becomes precarious. Therefore, it is fundamentally important to reflect on alternative models of development which enable enough thought to state and local issues and take the people along in decision-making.

India’s Constitution has a combination of unitary and federal elements to hold the nation together against internal and external challenges and yet provides enough power to the states to enable the diversity of regions, cultures, languages and socio-political desires and needs to find expression.

Much has been written about the current centralization push including the three agricultural laws, the National Education Policy (NEP) and the labour laws recently passed by Parliament. We believe that many elements of these laws are welcome reforms even as we are concerned about the specific issues of the mountains being ignored in these changes leading to further marginalization of the IHR.

When India adopted the Constitution in 1950 it was already clear in the minds of its framers that India would have to adopt a more centralized power structure than, say, the US. It is also well-recorded that the centralization impulse becomes more dominant when there is a strong single party at the Centre. The decentralization impetus finds some expression when the central government is a coalition government or is supported by regional parties. The pushes and pulls since then, between states and the Centre, have been well-documented by the Justice Sarkaria Commission in 1988 and more recently by the Justice M.M. Punchhi Commission constituted in 2010. The felt deficit in democracy and a consequent demand for decentralization over time led to the 73rd and 74th amendments to the Constitution which introduced a third tier of government, one that has unfortunately been implemented rather imperfectly in most parts of the country.

HOW CENTRALIZATION AFFECTS LIFE

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, India locked down completely on March 25, 2020. But what followed was simply a case of increased centralization both at the Centre and at the state level.

Parliament and the assemblies have been rendered ineffective during the pandemic, perhaps sidelined, willy-nilly. The states are staring at empty coffers and mounting debt. Consensus in Parliament which led to the setting up of the GST Council in 2017 to levy GST was hailed as a great example of cooperative federalism.The states gave up their fiscal autonomy — the power to levy sales tax in return for assured GST revenues for a period. The Centre has failed to honour its commitment to states to pay the planned guaranteed GST dues, citing poorer collections due to COVID-19. This issue is of immense significance for the future of Centre-state relations as it has to do with the credibility of the Centre.

The mountain states, in particular, are fully dependent on central grants and budgetary devolutions to run state finances. In the past, they received Plan funding from the Planning Commission besides devolution of taxes from Finance Commissions and streams of funding from centrally sponsored schemes. Ever since the Planning Commission was disbanded in 2014, the mountain states have lost a major source of funding. Today, in the absence of a Plan, the only resources to the states, besides the Finance Commission devolution, come as centrally-directed schemes which carry with them huge discretion by the central government. Recent examples of this include the linking of funding to the implementation of the New Education Policy and the new farm bills passed by Parliament.

COMMUNITY EMPOWERMENT

Integrated Mountain Initiative (IMI), a civil society organization, was set up by a diverse group of leaders from different states to understand the challenges and opportunities of IHR and bring all stakeholders together to resolve the complex and long-term issues of climate change adaptation, changing livelihoods, increasing risk of disasters, sustainable habitats, and water security, among others. IMI has engaged a large cross section of people from the Centre and the states in this effort as a volunteering, non-partisan and inclusive civil society platform. IMI realized early on that these problems don’t respect artificial boundaries of states and nations and therefore have to be understood in an unbiased and collaborative way.

IMI’s founding president, the late Dr R.S. Tolia, was invited as a member of a working group on Development of the Hill States commissioned by the Planning Commission in 2011. The resulting B.K. Chaturvedi Report recognized for the first time that in spite of providing ecosystem services to the country and having strategic significance because of the international border, the mountain states lacked the basic building blocks for economic development. The report found that the mountain states suffered a development disability and recommended a green bonus of two percent of gross budgetary support to the mountain states. This was, however, never implemented although Finance Commissions thereafter have begun to consider this issue in some measure.

More recently, IMI brought IHR issues to the attention of the 15th Finance Commission and leaders in each state. This led to all the mountain states coming together and representing their case to the Union finance minister, chairman of the 15th Finance Commission and the vice chairman of NITI Aayog. It is our hope that the final report of the Commission will be responsive to the articulated need of the IHR people.

We believe that the people of the IHR need to accelerate their journey to economic independence within the extant constraints and that this can only be done by better implementation of the 73rd and 74thAmendments and community empowerment.

We have the contrasting examples of Sikkim and Mizoram in the handling of the coronavirus epidemic. Mizoram was highly successful because it relied on its local and traditional grassroots institutions. Sikkim, on the other hand, was not because of its top down approach. There were no deaths in Mizoram and 59 deaths in Sikkim.

In summary, the IHR is landlocked with closed borders, sparsely populated and its people have very little voice in Parliament and in public policy formulation. It is a key geographical feature of the country contributing immense biodiversity, water resources and other ecosystem services. Centrally driven polices will not work locally. It may seem like swimming against the current of centralization but a new paradigm of state-Centre engagement is the need of the hour and one which is more decentralized in design.

P.D. Rai is president of IMI and former MP (Lok Sabha) from Sikkim.

Sushil Ramola is a former president of IMI.

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!