VENKATESH DUTTA

While working on the older Corona satellite pictures of Lucknow, I was impressed by the number of rivers that the city used to have in the early 1970s. A large network of streams is visible in satellite pictures connected with the Gomti river. There are big ponds — sometimes more than 100 hectares, holding water throughout the year.

As I looked at recent satellite pictures, I was disappointed to see that many of these rivers and ponds had disappeared due to the development of roads, colonies and shopping complexes. Apart from the Gomti, eight rivers used to flow through Lucknow, namely, the Raith, Behta, Kukrail, Bakh, Nagwa, Akraddi, Kadu and Sai. Out of these, four have disappeared in the past 50 years because houses, colonies and roads have been built on their beds. And three rivers are known as nalas or drains.

During the late 1980s and 1990s, many colonies came up on wetlands and terrace floodplains of rivers, rivulets and natural streams. Such structures caused irreversible damage to rivers and wetlands which are otherwise sought to be protected by law. Now every year, the groundwater level declines by one metre in the city as we have lost most of our natural recharge sites.

The public property of revenue villages like nalas, ponds, chakroads, pastures and the like was sold to builders and land development agencies. The Lucknow Development Authority (LDA) built colonies on big ponds. According to satellite pictures 70 percent of the city’s ponds have disappeared in the past four decades. When there is rapid decline in recharge areas, how will groundwater be replenished? Agencies like the municipal corporation and LDA take the side of the builders and colonizers. In January, a case of encroachment of ponds in Gomti Nagar came up in the High Court. In Gomti Nagar extension, buildings were constructed on the land of 17 ponds with the full knowledge of the administration. Why are the people in charge playing with the future of the population?

Many smaller rivers and rivulets in India are disappearing. Many of them got converted into sewage-carrying drains, while others were encroached upon by private and government colonizers. No legal provisions have been made to protect the land adjoining these rivers. In many cases, roads and houses were built on river banks, reducing the flow path of the river. Many upcoming cities do not have a master plan, and those with master plans are least concerned about natural streams and wetlands. The choices that have been made about urban growth and governance have repeatedly ignored encroachments on the floodplains of rivers, which has led to the destruction of a number of ponds, wetlands and water systems that were once linked with the river. Our cities have also experienced an increase in the frequency and severity of flooding incidents as a direct consequence of the removal of a number of these naturally occurring sponges and the consequent lessening of the flood-carrying capacity of the rivers.

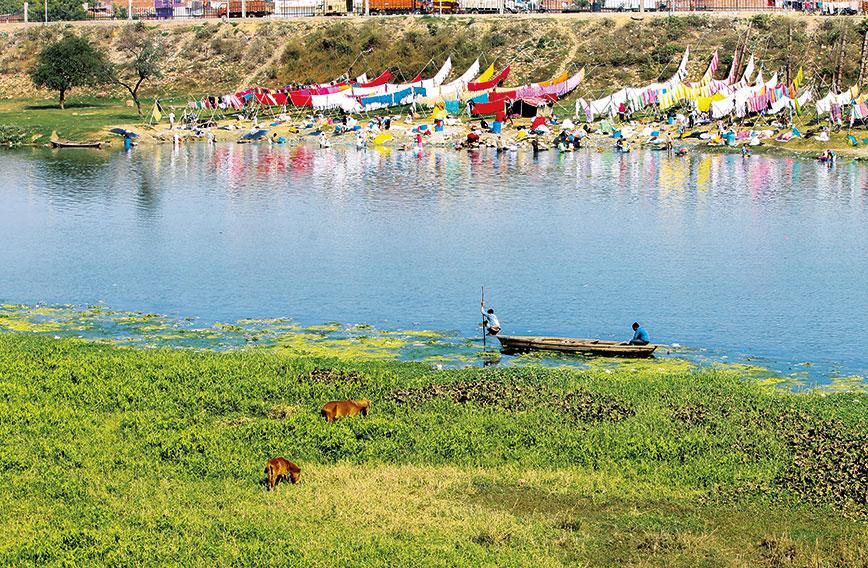

The Vishwamitri in Vadodara, Musi in Hyderabad, Godavari in Nashik, Gomti in Lucknow, Mutha in Pune, and Noyyal in Coimbatore are only some examples of how these rivers have been severely mistreated as they flow through the cities. Their smaller tributaries are disappearing fast from the map. The rapid pace of urban development with negligence toward drainage systems of our cities and their suburbs have caused the rivers to recede into the background. Sewage and industrial effluents discharged into the river, polluted storm water outfalls, and many other sources of pollution have all wreaked extensive ecological degradation.

A deeper look at the master plans of some cities reveals that urban growth is legitimizing large-scale land use changes — often transforming natural river banks into publicly accessible river promenades, similar to the highly publicised Sabarmati Riverfront Development in Ahmedabad. Creating channels that are lined with concrete will alienate bank vegetation and prevent groundwater from getting in along the river. A more strategic priority would be to lessen the amount of impermeable surface area in the entire segment of the river.

Master plans address the rivers in a piecemeal manner, to the point of ignoring the larger watershed and hydrological network of which a river is a part. The idea of modifying the riverbanks and holding water all year long will impair the entire biological function of a perennial river that undergoes many seasonal changes; it can transform the river into an impounded pool of water that has lost all ecological integrity. Important biological niches will be lost if the riparian areas are paved over with concrete, as this would prevent vegetation from growing there.

Once upon a time, rivers and streams were focal points of our collective consciousness, celebrations, cultural identity, memories, rituals, tales, and daily needs. Now, cities are restructuring the hydrology of urban watersheds, resulting in distorted dynamics of recharge, flooding and even vegetation cover. The administrative zones or limits are always used as the criterion to determine the development zones, while ecological boundaries are ignored in consideration during the development process. We need to reverse this trend. Ecological boundaries should get prominence over administrative boundaries in our master plans.

We need master plans that don’t merely have the purpose of making the river an amenity for humans to use; rather, the goal should be to protect the ecological integrity, improve the health of the ecosystem, enhance natural biodiversity and integrate the socio-cultural identity of the place. Smaller streams, rivulets and rivers can transform a city’s landscape and can be great natural assets. They can also improve the quality of life of people. But only when we decide to protect our water endowments.

Venkatesh Dutta is a Gomti River Waterkeeper and a professor of environmental sciences at Ambedkar University, Lucknow

Comments

-

Dr. Narasimha Reddy Donthi - April 17, 2023, 10:33 a.m.

Quite true. I have been suggesting inclusion of water zones in zone-centric Master Plans. This can help in protecting catchment areas, feeder channels and rivers, from land use change.