Anindya Hajra: ‘We have hosted several collaborations this year.’

Kolkata queer month goes beyond Pride

Aiema Tauheed, Kolkata

WHEN the Queer Arts Month 2.0 opened in Kolkata recently it marked yet another step forward in the long and complicated quest for a better understanding of people with different gender and sexual identities.

The show was put together innovatively by Navonil Das and Anindya Hajra to convey that there is more to Pride than celebrations and slogans. It went on to accommodate all voices and experiences seeking equality.

Interestingly, the Kolkata Queer Arts Month 2.0 came around the time when the Supreme Court upheld its earlier order disallowing same-sex marriage, but giving people the right to live together.

The queer rights movement has had a long and arduous journey. It has been through courts and legislatures with successes and failures. But the challenge that has been most difficult to cross has been the elementary human one of being accepted as a part of one universe with everyday choices and concerns.

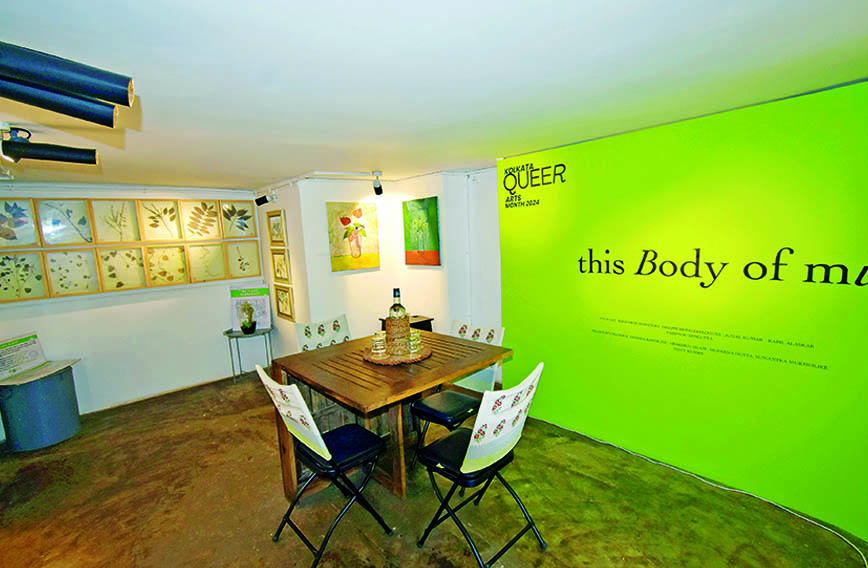

It is to this end that the Kolkata Queer Arts Month was conceived and first held in 2023. The November event, with “Ghosts and Ghettos” as its theme, built on the first. It was held at three locations: Aranya Baari, a café, Anjali-Pratyay, a space for assisted living, and Experimenter, an art gallery.

With an open call for submissions and invitations to a select few, the exhibition featured artworks by about 25 artists. These artists are people who are both queer and allies.

Says Das: “They are not all queer. I said that if we want others to be inclusive, we must be inclusive ourselves. That’s why Kolkata Queer Arts Month is open to everyone. Many artists are allies who have a strong political voice, and we welcome them.”

The abbreviation LGBTQIA+ is itself a constantly evolving one. It stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, agender. The plus sign holds space for inclusivity, an ever-expanding swath of the community, with a growing understanding of gender identities and sexual orientations.

“We didn’t want to position ourselves as curators, per se. Last year, we invited Kallol Datta, a textile artist and designer, specifically to take on that role because we weren’t sure what form or shape the event would take. Kallol gave it a great structure,” says Das.

“This year, we thought about doing things differently, especially with a budget cut in place. But you wouldn’t be able to tell,” he remarks with a chuckle, looking around at the bold and brilliant artworks at the café.

Why “Ghosts and Ghettos” as the theme? “As marginalized people, we continue to carry the ghosts of the past and are confined to the ghettos of the present,” says Das. The ghettos, he says, are not just places but states of being.

This Body of Mine on a vivid green wall welcomed people at Aranya Baari. Das tells us that in queer politics, the body plays a crucial role. There is the trans body, the queer body, bodies of different shapes — some visible, some hidden.

These bodies are often judged for existing outside heteronormative expectations, especially regarding sexuality.

“So, This Body of Mine is a way of urging you to look within yourself. We are exploring our bodies through art,” he explains.

There was a wall dedicated to the East Kolkata Wetlands and it was called Disappearing Dialogues. The wetlands have been gobbled up by real estate and with them have gone plants and other organisms. This used to be a unique natural recycling system using sewage to grow fish and garbage gardens to cultivate vegetables.

Frames containing medicinal and edible species were on display. Next to them were abstract ink drawings on Fabriano paper. But what could plants have to do with rainbows?

“Ecology of nature and ecology of people cannot exist in silos. Conversations on sustainability are not complete without addressing our current socio-political situations,” explains Das. “These leaves, gathered from wetlands so close to us, remind us of what we’re losing out on.”

Das, popularly known as Nil, is a queer fashion designer who wears his identity on his wrist through a signature Pride band. His pluralistic worldview shone through in his friend, Eina Ahluwalia’s pendant called the ‘Mandir Masjid pendant’ resting on his chest.

A recipient of the Tertiary Art Prize in Australia, he returned to India in 2004 to launch his label, Dev r Nil. Raised in Bengal’s paraa culture, he began as a volunteer, serving as a sexuality officer in college and supporting Pride events in Kolkata. He also happens to be a founding member of The India Story which is now in its 10th year.

PINK PARTIES

Das and Hajra are pivotal to Kolkata’s queer rights movement. About 15 years ago, when Hajra, visibly trans, was barred from entering a club, it sparked the inception of Pink Parties here. These now serve as the fundraising backbone of Kolkata Pride, with a significant portion of the funds for Queer Arts Month 2.0 coming from them.

Navonil Das: ‘Many artists are allies and we welcome them’

Navonil Das: ‘Many artists are allies and we welcome them’

A small flight of stairs leads us up to the dining space of the café. Shaded lamps, fairy lights, books, rare old LPs in a basket and some plants give the café its quaint, rustic charm. Bold and life-sized paintings cover every wall.

Social maladies, cloaked and caked in dirt, are laid bare on canvases, brazen enough for onlookers to gasp. There is the searing depiction of Draupadi’s disrobement from the Mahabharata in watercolour and ink on acid-free paper, surrounded by painted eyeballs depicting the male gaze in the courtroom. Titled Panchali in the Court, this piece is part of an original graphic novel by Sankha Banerjee.

On another wall hangs Vijay Kumre’s The Red Light (2024), in which an actual red light glares through a canvas of jute. Next to it is a nude woman, with dull, bloodshot eyes. “Well, it is, quite literally, a depiction from a red-light area. Talks of prostitution and women from the marginalized sections there,” Das explains.

In a room just a flight of steps away lie two life-sized cloth canvases by Sriparna Dutta, whom Das describes as one of the most celebrated artists this time. Sriparna, a multidisciplinary visual artist and former IB educator, works with women at grassroots level. She greeted us with a bright smile alongside her silver-haired mother, who had kindly eyes and an even brighter smile.

MOTHER AND MUSE

As they stood proudly beside the artwork, it felt as though the fabric had come to life, artist and muse extending seamlessly into flesh and blood. And why not? Titled Interlaced Narrative (2024), stitched onto the canvas of her mother’s saree were two large figures — Sriparna and her mother — surrounded by caricatures of women in various poses: some washing dishes, one standing tall, and another peering directly at us.

Sriparna Dutta and her mother with her artwork, ‘Interlaced Narrative' (2024)

Sriparna Dutta and her mother with her artwork, ‘Interlaced Narrative' (2024)

As a child, she watched her mother, a house nurse, spend 30 tireless years juggling daylight hours and gruelling night shifts, all for the sake of her child’s future. But in 2020, she took a step beyond the role of a daughter to truly see her mother as a woman. That’s when the stories surfaced — of abuse and sexual violence, of strained household dynamics, and of economic hardships.

Those revelations became a turning point for her. In 2021, she was out travelling and meeting women in different work settings.

“Who is this?” we ask her, pointing at a caricature of a woman who seems to be doing dishes, “I met her in Nala Sopara, a small village in Mumbai, where she was caught up with her daily chores. Her hands never stopped, moving deftly from one task to another, yet she was kind enough to talk to me,” she fondly recalls.

Pointing at another caricature, her eyes soften again, “That’s Devika, she’s in 9th grade. Her mother, Sushma Didi, is a worker. I spent a birthday with the family,” she says.

WOMEN’S LIVES

Sriparna is currently working on two research projects. One of these projects is on economic discrimination, where she’s asking women one simple question: How would you spend a hundred rupees?

“For one, it’s not even enough to splurge on a coffee latte. For another, it’s a hearty meal of biryani. And for yet another, it’s the investment in a packet of cigarettes to keep her customers coming back to her chai dukaan,” she explains.

|

|

Archee Roy with her artwork, ‘I, Exist’ |

The other is a project on 21st-century women. Among whom stands a domestic worker, violated by her malik, forced to show up each day because survival doesn’t afford the luxury of refusal. Another, locked inside her home by an office-going husband, stares at a door that separates her from a world she’s never known. And yet another, raped by her in-law while her husband watches in silence and hopes for the birth of a baby boy. And many, many more.

These are all women etched onto the fabric of both her artworks exhibited at Aranya Baari and Experimenter, the third site.

At Experimenter, she has an ongoing handmade cloth book of these women. One that allows the visitor to pick it up, flip through and place it back, etching their own touch onto it. She wanted her art to be touched and felt by all, in an attempt to shatter the elitism that comes with art.

Anjali-Pratyay, which is a site of the exhibition, provides assisted living for recovered mental health patients. Taxi drivers can only identify it as a pagal khana. But it is far from what an asylum looks like. Residents, some with family and many without, live in harmony, spending their days baking, attending workshops, and stitching.

Abhijit Sengupta of Anjali-Pratyay showed us around. Kind eyes and smiles greeted us. Some were too busy pouring batter into moulds or stitching to notice us.

By this point, we couldn’t help but wonder why the exhibition had to slip out of an art gallery.

“We wanted to examine whether the gallery space itself can become a kind of ghetto. How do we dismantle that? Do we, by operating within the art world, confine ourselves to the white cube of the gallery alone?” explained Hajra, a founding member of Pratyay-Gender Trust.

At Anjali-Pratyay, a large wall read: ‘We can always go’. The library and an adjacent room were turned into exhibition spaces. In the large room, a table displayed ceramic objects that caught the eye. “Everything on this table was created by our residents,” says Sengupta, beaming proudly.

The collection included a ceramic turtle, fish, coasters, spoons, plates and more. All in great shape. “They were delighted to see their work on display,” added psychologist Suhita Surai.

Next to the table was a large canvas titled I, Exist with brushstrokes resembling the lines of a topo map, eyes and handprints scattered across. This work was created by Archee Roy, a Dalit queer visual artist and activist with Sappho for Equality. “These are my hands. I try to imprint myself in my work so that I exist wherever I go. The system won’t give me space to exist, but I will claim my own,” she said. What began as activism for Archee soon turned into a realization that art could also be a powerful form of expression. She is currently studying textile design at Kala Bhavan, Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan.

‘This Body of Mine’ is a way of looking within. It is the exploring of one’s body through art.

“We are facing systematic oppression,” she said gravely. “It’s about surviving every moment.” Her works are inspired by socio-political complexities around us. “You’ll also notice a fish in this artwork. When something happens to one, they all come together, galvanizing into a cluster,” she said.

Recalling a dialogue by Paresh Rawal’s character in Bhool Bhulaiyaa, “Jhund banake chalo,” she talked about the politics of jhund. “We move in clusters because we know we can’t fight alone,” she explains. “It’s very different from the history of ghettos in Black American society. We know that we can’t fight alone. We have to ghettoise. We’re claiming ghettoisation.”

To her, this jhund stands for solidarity for survival. She uses broomsticks and large brushes, painting freehand to make her work “instinctive.” I, Exist, an acrylic painting on a three-metre-long canvas, took her three days to complete. The dynamic, unpredictable lines in the work explore the tension between chaos and resilience. The eyes featured in the piece serve as mirrors, speaking truth to power.

At the Experimenter Art Gallery was featured a segment from artist-activist Sheba Chhachhi’s Seven Lives and a Dream, a series of monochrome photographs from the 1980s’ anti-dowry protests. The intense eyes of women which seemingly follow you, honour the feminist activists of that time.

As Ahon Gooptu, gallery associate, said, “Maybe that’s the point. Their gaze follows her in her work. She has documented her foremothers.”

Overall, it took Das and Hajra exactly a month to prepare this Queer Arts Month. “This year’s edition saw more spontaneous submissions than the last one. It is perhaps due to greater awareness after the first edition. We also hosted several collaborations, including a workshop with contemporary dance practitioner Sudarshan Chakraborty and the girls of Ektara School,” Hajra says.

“The intention was to go beyond the textbook definitions of what it means to be queer or trans, particularly within the arts space. This is precisely where this edition of Kolkata Queer Arts Month has made its mark, as a trans and queer-led initiative,” Hajra continues.

At Experimenter, surrounded by artworks and poems, with the line ‘Rust is our redemption’ on the wall, Anindya shared a glimpse of the next edition, which will feature a retrospective on trans and queer lives in India.

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!