Rethinking the smog

IT is 6.30 in the morning and you are starting your day in Gurugram. A thin fog, more like a mist, hangs low outside. You check your phone for the weather report to see if there could be rain coming. Along with the weather, you check the Air Quality Index (AQI). It is at 162 at the level of unhealthy. This despite your neighbourhood being leafy and greener than most. In Delhi, where you will spend much of your day, the AQI is 159 at that hour and you wonder how much worse it will get.

Tracking of air pollution has become an everyday activity, particularly so for people in the National Capital Region (NCR). Data is collected from thousands of monitoring devices and made available in real time, instantly, on the screen of your phone. Comparisons are now possible between cities and regions.

AQI has entered common parlance. So has GRAP or Graded Response Action Plan, which kicks in with curbs at different levels of pollution. Both have been around for a decade but air pollution has only become worse. So, what’s going on?

A recent inventory-based nationwide study of PM 2.5, that very tiny particulate matter that goes deep into the lungs, suggests the problem is the targeting of the wrong sources of air pollution.

Automobiles have been prominent in the crosshairs of regulators and activists. But instead, they should have been going after the open burning of solid fuels like wood, dried cow dung cakes and coal.

Biomass ranks as a huge problem because people continue to use it widely in their homes for cooking and keeping warm. Similarly, garbage disposal is inefficient with the result that much of it routinely gets burnt.

When biomass is burnt it generates pollution that goes directly into the atmosphere without any safeguards. Machines (think vehicles) can, by contrast, be controlled for emissions.

The study has been done by iForest, an environmental non-profit, whose founder, Chandra Bhushan, is a veteran in the sphere of pollution control.

Says Chandra Bhushan now: “The urban-centric and automobile-centric focus is the reason why we have not been able to address air pollution holistically.”

|

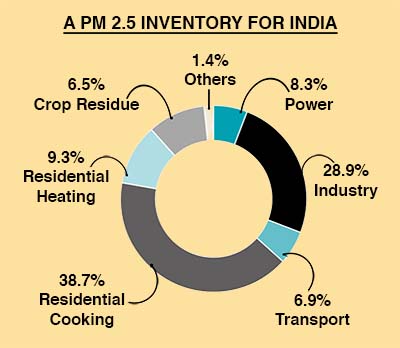

At the national level, Bhushan says, the iForest study found that 55 percent of PM 2.5 across India came from biomass burning. Of this 55 percent, around 48 percent came from cooking and heating in homes and 6.5 percent from crop residue burning in the fields. From industry came 28.9 percent and from power plants 8.3 percent. The entire transport sector accounted for just 6.9 percent, according to this study.

iForest did a second study of PM 2.5 in only Delhi and the NCR and it showed roughly the same proportions. Once again, biomass accounted for the bulk of the pollution with the following break-up: residential cooking 41 percent, heating 10.5 percent, stubble burning 10.5 percent. Transport only accounted for 5.9 percent. Industry was at 25 percent and power 5.9 percent.

Delhi’s pollution has also to be understood in relation to its peri-urban areas and the rest of the NCR. The major part of Delhi’s pollution, perhaps 60 percent or so, comes from these surrounding areas and 40 percent comes from within Delhi. But for both Delhi and its surroundings taken together the biggest source of pollution is biomass burning.

Much heavy lifting is involved in dealing with such sources of pollution. It means engaging with communities at the household level, social marketing of cleaner practices and providing deterrents and incentives. Getting people to transition to safer fuels at the household level is a slog as is promoting segregation of garbage and recycling of solid waste instead of leaving it around for people to burn.

Since these aren’t glamorous measures, they tend not to get done. There is greater visibility in cracking down on automobiles and bringing in electric buses — both of which are seriously needed — but are not enough to bring down pollution.

GLOBAL EXPERIENCE

“India can only reduce its pollution if it can reduce its use of biomass and solid fuels. The reason is clear from the numbers. If you take power plants and industry together, you are talking about 35 to 36 percent. But cooking and heating fuel together account for 50 percent. This is what the basket is. So, for us the focus has to be biomass and solid fuel,” says Bhushan.

|

| Chandra Bhushan |

“You know, this is also the global experience. No country in the world has reduced pollution without focusing on solid fuels. In China, before the Olympics, their entire focus was on solid fuels. They started shutting down coal-based power plants. They started providing LPG (liquefied petroleum gas),” he says.

“It is also true of the cleanest countries in the world as far as air pollution is concerned. You will not find them burning solid fuel,” he adds.

This can be said of the more developed, prosperous and better governed parts of India as well. In the southern states, for instance, LPG is more widely used and so pollution from open fires is less of a problem.

A kilo of coal or wood burned by a domestic user does more harm than a tonne of fuel burned in an engine with pollution control devices. Pollution from an open fire goes directly into the atmosphere. There are no filters.

Families in slums, the large numbers of security guards trying to keep themselves warm on cold nights, tandoors at small eateries all add to pollution in the NCR and elsewhere in the North in ways which are not being assessed.

Sources of air pollution can be put into categories such as combustion, non-combustion and natural. Combustion clearly is what gets burnt whether it is fuel in a car or plant or biomass in a poor home or the burning of stubble in fields or garbage at a landfill. Non-combustion would refer to dust and chemicals — from a construction site, for instance. Dust could also be natural and similarly forest fires though caused by combustion.

REGIONAL APPROACH

Air pollution traverses distances so a regional approach is in order. The smaller cities, peri-urban and rural areas of the NCR and in the North are inextricably linked. Smoke from stubble burning in the fields of Haryana and Punjab add to pollution in Delhi. Forest fires in Uttarakhand similarly impact the region and reach Delhi.

For its study on the NCR specifically, iForest found it necessary to go beyond the NCR to include the four districts of Aligarh, Mathura, Agra and Hathras because they are all known to be major sources of pollution and in the proximity of the NCR though not formally part of it. Interestingly, their sources of pollution and the proportion were more or less the same as the NCR itself.

The spread of LPG is uneven and firewood continues to be used in kitchens

The spread of LPG is uneven and firewood continues to be used in kitchens

It is a myth that rural areas are not or less polluted. The issue is cooking fuel. The National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) data, says Bhushan, shows that 50 percent of rural India has made the transition to LPG. But this data needs to be tempered with the reality that people have LPG but also use biomass and coal as cooking fuel.

“Overall, our estimation is that close to two-thirds of rural India is primarily reliant on biomass. And close to 20 percent of urban India is reliant on biomass and coal together,” says Bhushan. “We did a study in Ramgarh district in Jharkhand. We found 60 percent of Ramgarh district and the city of Ramgarh is reliant on coal as cooking fuel.”

The reason a solution to air pollution has been elusive even though it takes a heavy toll on the economy is that there is a lack of focus on the real nature of the problem.

“Our focus has been cities because our focus has been the automobile. And in this, we have forgotten about two-thirds of India’s population,” he says.

Cities too are unevenly developed. The poor people in large numbers and in the peripheries have been absorbed without the civic infrastructure or access to urban services. What has ensued is a chaotic situation far removed from stable urban management and standards. As much as rural India doesn’t get the attention it deserves equally peri-urban areas are overlooked.

“We examined 20 years of research and found paper after paper showing that rural areas are suffering equally from air pollution. Researchers have been talking about it. In fact, more people have been dying from pollution in non-urban areas than in urban areas,” Bhushan says.

|

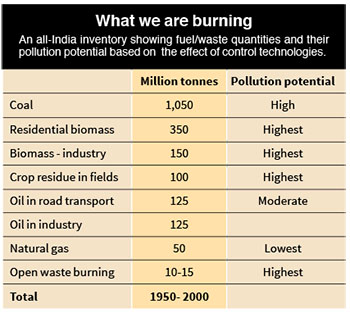

An inventory put together by iForest shows India burns around two billion tonnes of material. Of this, one billion tonnes is coal and 350 million tonnes is biomass in the residential sector. Industry burns 150 million tonnes and in the fields 100 million tonnes is burnt. Only 125 million tonnes gets consumed by road transport. About 125 million tonnes of oil and 50 million tonnes of natural gas is burnt in industry. About 10 to 15 million tonnes of waste is burnt.

“The problem is that everyone is looking at pollution from their own vantage point. Someone’s focus is the automobile, someone’s industry. A comprehensive picture has been missing,” says Bhushan.

“The legacy of environmentalism in India is rich vs poor, urban vs rural, industries vs cities. It comes from the left. People are not looking at the problem dispassionately. A lot of values get into their thinking, the choices they make. There is a tendency to leave the poor where they are while going after that SUV and industry,” Bhushan rationalizes.

Would he say that the many efforts to reduce automobile pollution were wasted time and effort when addressing solid fuels would have been more effective?

“I am not saying that. But I will say there should have been a parallel initiative. The focus on the automobile was right for the urban areas. But the singular focus was wrong. It hasn’t solved the pollution problem in 20 years. We should have also focused on energy transition in cooking fuel. Today it is because we are at Euro 6 that automobile contribution to 2.5 emissions is 6.5 percent. Had we continued as things were in 1990, when we were non-Euro, it would have been 15 percent,” he avers.

CHINA’S EXAMPLE

India can learn from China. A regional approach was followed to bring down Beijing’s pollution. A target was set for PM 2.5 emissions and to make it happen there was regulation, fixing of responsibility in the government, enforcement and a transition to better technologies. Clean cooking and heating fuels were brought in. All this resulted in PM 2.5 levels falling by 30 percent between 2013 and 2017.

As in Beijing, most of Delhi’s pollution comes from its surrounding areas. The figure varies but around 40 percent of Delhi’s pollution is from within its boundaries. The rest is from outside. Delhi also represents only a small part of the NCR. A regional approach therefore becomes essential. It is also important to improving the quality of life in the NCR generally. This would also hold true for other parts of the country where pollution is rampant and cannot be addressed piecemeal.

According to a report recently put out by the Swiss company, IQAir, Delhi is the most polluted capital in the world. But a more important revelation in the report is that Byrinhat in Assam tops the list of polluted metropolitan areas. Byrinhat has never been in the news but it has consistently high pollution. Its problem too is regional, being located in Assam but also close to Meghalaya.

LOCAL GOVERNANCE

The report also lists 13 Indian cities as being among the top 20 most polluted cities in the world. The list of course has Delhi, Noida, Faridabad and Gurugram in it. But also in the list are Loni, Bhiwadi, Hanumangarh and Mullanpur.

The thing with pollution ratings is that they represent the tip of the problem. Below is a morass which is difficult to envisage. For all the lesser-known cities mentioned in the IQAir list, there are innumerable more in India which are horribly polluted. They would all have poor infrastructure, depleted municipal finances and little or no access to expertise to help them emerge from the mess they are in. Air pollution would be adding to their disease burden with every passing day.

A fire smoulders at one of Delhi’s overburdened landfills

A fire smoulders at one of Delhi’s overburdened landfills

As India urbanizes, dealing with pollution in cities will require a national effort. Since cities are broke, they will have to be financed and encouraged to bring in expertise and technology. But at the same time there can be no substitute for city-based and regional action. There will have to be the social marketing of measures and creating of awareness. Mayors and councillors will need an upgrade in their political status so that they can personally lead a transformation. Local administrations will have to persuade people to stop burning garbage and give up using firewood. They will have to put the alternatives in place too. Getting air pollution under control will mean waking up to the long-term harm that it is causing and going beyond GRAP and AQI. A new language is needed. Delhi’s measures have been replicated from the developed world which is why they are limited in their success. A better understanding of local realities is in order.

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!