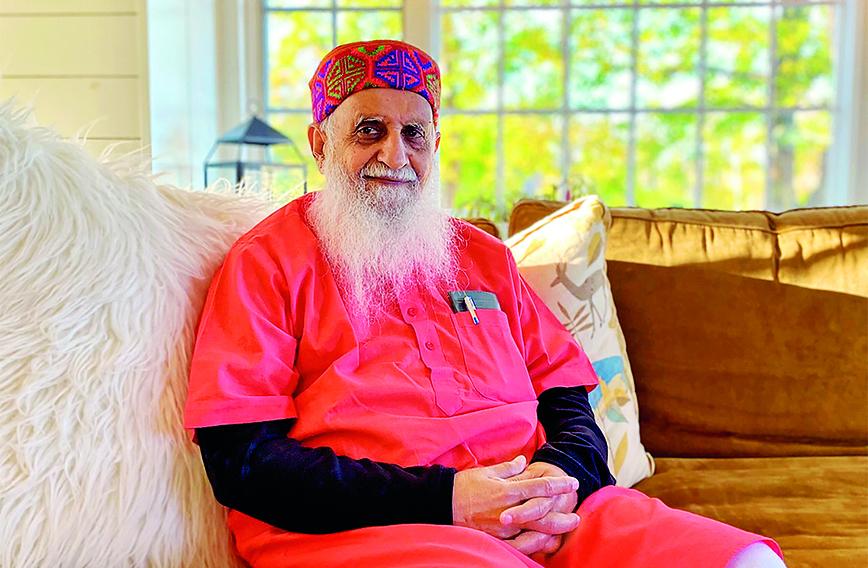

Ravi Chopra: ‘It’s very hard to be heard anymore’

‘Himalayas on the verge of a crisis now,’ says Ravi Chopra

Civil Society News, New Delhi

WHEN he set up the People’s Science Institute (PSI) in Dehradun all of 40 years ago, Ravi Chopra, with an IIT degree to boot, was well ahead of his time in his concern for the Himalayas.

He remains one of the most honest, socially driven and scientific minds on the needs of the mountain states, which are now faced with a growing environmental crisis.

Chopra has served on an empowered committee appointed by the Supreme Court. It is to his credit that he has always been eager to engage with government. It is also his hallmark that he stands up for communities and their rights.

Civil Society spoke to him about the Ladakh agitation and more. Here is an edited version of our interesting interview.

Q: What did you think of the protest in Ladakh, Sonam Wangchuk and others walking all the way to Delhi, going on a hunger strike?

What is most striking for me is that people feel compelled to do these desperate acts in a country that is supposed to be a democracy. We have elected representatives. We have governments. And yet, the only way we can be heard is to hit the streets. And most often, even that doesn't work.

We must recognize the courage that these people have taken and they’re sticking to their principles. They have been very orderly. They have been very systematic and they are totally non-violent. Those things have to be appreciated.

Q: As an environmentalist and an engineer, you have gone out of your way to engage with people in authority who might not be seeing the world your way. Why is it difficult to engage?

That depends on the government. Until 10 years ago we had governments that always gave people a place where they were heard — and I am not saying one government, I am including the Atal Bihari Vajpayee government and state governments.

There were all kinds of representatives and you could walk into their homes, whether they were MPs or ministers or whatever. You could go up to the government, or governor in your state. We still do that. And you could be heard. But in the past 10 years, I’m sorry to say, the NDA government shows no willingness to interact with the common people, to listen to their problems and complaints. And this has been a systematic record. The farmers, the wrestlers, the environmentalists….

Q: The oversized presence of corporations in our lives is not new. But is there a preponderance of corporations influencing decision-making and coming together with the political class? Do you think you’ve reached the point where you can’t talk to anybody because the quantum of power that you’re dealing with is so enormous?

Yeah, there are a lot of people who believe that to be a factor, the coming together of certain very large corporations and the political class is needed. That’s there. But I think (this attitude) has gone down the ladder. We find that our chief minister doesn’t have time to talk to protesters who come from Joshimath. He gives them about two minutes late in the night. The district magistrate doesn’t have time to talk to the people of Joshimath. So it’s just going down the ladder now. It’s very hard to be heard anymore. News media, you know better than me, is captured by one side.

Q: The solution to this, therefore, is to have a different kind of politics.

Yes, it’s far more important to have a different kind of politics than different political parties because, you know, when they function within a given milieu they all tend to become like this. I mean, you see the Congress-run governments.

Q: Sonam Wangchuk has raised the issue of not just Ladakh but the entire Himalayan region. And he has said that we need to ring alarm bells about the environmental issues that affect all the states in the Himalayas. What would be your primary concerns?

My primary concern is that we are standing at the very edge of a tipping point, beyond which are catastrophic impacts and possibly irreversible climate change. And I don’t think the government is displaying a good understanding of what’s in store for us. It may have that understanding. I don’t care about that. It’s not displaying it. It’s not there in its words and actions. To begin with, the whole Himalayan region is geologically fragile and ecologically sensitive. Extreme impacts on it are going to be devastating.

Q: So, what you are saying is that you have climate change, a fragile Himalayas and a government that is not responsive?

Can I elaborate on this? We know that there are certain kinds of disasters that are sitting over there. I can see them. And I need to be prepared today if there is a disaster tomorrow. I need to be in disaster mitigation mode. I need to have disaster resilience built into the development, so-called development programmes. We don’t see a comprehensive understanding.

Q: Is the government living in denial?

To a large extent, yes. It’s basically an anti-environment government to begin with.

Q: What is it that you fear in the next few years for the Himalayas, especially where you are in Uttarakhand?

What we see are two major manifestations of climate change in the Himalayan region. One is temperature change and the other is precipitation pattern change. There are rising temperatures everywhere. If you look at the foothills, the habitations below 1,000 m or so, temperatures are soaring to 40°C in the summer. And for extended periods. Are we preparing to meet this challenge? By the end of this decade, we could hit 50°C. Are we thinking in terms of heat shelters? I haven’t heard the word. Are we thinking in terms of decongesting our concrete jungles? Or relocating economic activity, dispersing it, dispersing tourism, lowering temperatures?

You take the precipitation pattern. We have less winter precipitation. The rainfall in summer is becoming more intense, in shorter spells. And the phenomenon of western disturbances, which used to be primarily a winter event, is now there also in summer. When the western disturbance collides with the summer monsoon clouds, it produces disasters. Are we redesigning our roads? No. Are we redesigning our dams? No. Are we trying to reforest and green our cities? No. So I don’t see the mitigation measures that could have been possible.

Q: Paint some kind of a scenario. What would you see happening?

Let’s begin with what’s happening at the top. Glaciers, we are told, are melting. But, you know, many of the glaciers are small. The ice pack is not uniformly thick. So, some parts of it where the ice pack or ice mass is less, they are melting and forming lakes. As a result, there’s fragmentation of glaciers. Lakes are being formed. The number of lakes is increasing and therefore the probability of GLOFs (glacial lake outburst floods) is increasing. GLOFs will increase. And the attention of researchers and the governments is on that. Poor Sikkim tried and it couldn’t do anything because their machine wouldn’t work at that height. You need to prepare disaster prevention plans now. What is going to happen in the river valleys when that flood comes down?

If you come down to slightly lower levels, let’s say 1,500 to 2,500 metres, that’s where our hill stations are located. And these are areas where we used to have lots of springs and small mountain streams. Now, warmer winter and spring, less snowfall, less precipitation in the winter and the springs are drying up. What has the government done about it? In the past decade, NGOs with local communities and some state governments in the Himalayan region have revived thousands of streams. Himanshu Kulkarni (a hydrogeologist) gave me a figure of 10,000 springs being revived. Where is the government programme on this?

If the aquifers and the springs dry up then the base flow of rainfed rivers disappears. Then what happens to the paddy nurseries that have to be created around the end of May? You know there’s no water in your rainfed river. The Kosi in Uttarakhand does not have water at that time. So, it affects agriculture. If water supply in those rivers is reduced, it affects water supply to the nearby areas for domestic purposes.

In urban areas, we are creating heat islands. Citizens for Green Democracy in Dehradun went around the city on May 28-29, recording temperatures at various locations. At Clock Tower, on the tarred surface of the road, the temperature was 65°C. What was the temperature of the ambient air? 42°C. Under the big peepul at Clock Tower, it was 37°C. And I have several such recordings made by them at different locations which indicate very clearly that we are creating heat islands. The shade of a building is much hotter than the shade of a tree.

We have approved plans to cut down 65,000 trees in this valley. Several thousand have already been cut in Dehradun. And my figures are that about 25,000 trees throughout the valley have been cut already. This number will go up to 100,000 trees or more if the pending plans are approved. Doon Valley was the first eco-sensitive zone that was created in the country. Does anybody care?

Q: What would be the mechanisms you would propose for better decisions to be taken?

The first thing I would propose is to push the forest department back into reserve forests. That’s all that they can manage. I’m not saying that they can do a great job, but they can manage it. At the time of Independence, the area under the forest department was roughly about 33 to 35 million hectares. Today it is 70 million hectares.

Where did that come from? From the Rajwade and the community forests. They have gradually weakened community institutions and taken over their forests. The van panchayats of Uttarakhand have been ruined. When forests are ruined, there is no water and you can’t cultivate, so what will people do? They will migrate to the city.

We can put in checks and balances and you can work with people because their lives depend on those forests. I’m advocating community ownership of natural resources, both of jungles as well as of water.

Q: The government needs to build roads on the border, right? What kind of consultative machinery do you think should be used?

Well, in most of these issues you are going to impinge on some natural resource base in some region, right? If you had community control, let’s say in PESA [Panchayats (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act] areas, at least on paper people have those rights. So at least include those community representatives in your decision-making bodies. And not just one or two representatives. I have found repeatedly that in decision-making bodies, people’s representation is just a token one and therefore very weak. They have to be a majority.

Q: Wouldn’t this be unrealistic? I mean, these are decisions which involve national security. Can you imagine a situation in which the government is in a minority and communities are the majority and control decision-making?

Such decisions would impact the communities staying on the border more than anybody else, right? It’s a well-established fact that our borders have to be protected by citizens living there who are dependent on that land. Look back and think. When an Indo-Pakistan war breaks out, who supplies food to the Army, putting their own lives at risk?

Why is the government so scared of Sonam? My guess would be that Sonam has probably better information about the state of our border in Ladakh than the Government of India (GoI) does.

The government makes noises about bringing development to border areas. You need people settled there and their lives are going to be affected. They are not going to fight with the Defence Department. People are willing to give and take. I don’t see unreasonableness by them.

Q: If you don’t have a politics which trusts people, works with them and understands their needs you won’t be able to achieve a stable form of development where environment truly matters, right?

Yes. Look at the whole story of Char Dham. The committee gets set up. It’s heavily in favour of the government. Ultimately, the HPC (high-powered committee) report reaches the Supreme Court. The judge says all that the minority is saying is to implement your rules and regulations.

He passes an order that instead of having a 10 metre-wide tarred road surface, according to your own rules and regulations, come down to a five-and-a-half metres tarred road surface. At that hearing, the Defence Department submitted an affidavit, in September 2020, saying they needed only seven metres of tarred road surface.

Tushar Mehta, the solicitor-general, tells the court, since Mr Chopra is saying five and a half metres, we are willing to agree to seven metres for defence purposes. After that, when we try to get that five-and-a-half metres order implemented, there is stonewalling. A new appeal is filed by the GoI. Another hearing date is fixed. The Defence Department files a new affidavit asking for seven metres. The Ministry of Road Transport and Highways (MoRTH) files an affidavit saying it wants 10 metres.

The judge says, you are two departments of the same government. Can you please sit down and resolve your differences? Fifteen days later the meeting takes place between the two departments. And what do they do? They supersede the old regulation of MoRTH on the five-and-a-half-metre regulation for the hills and the new regulation now is 10 metres.

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!